I write this on the evening my son has finally finished the first part of the huge challenge, the French Concours for Medicine. In this article, I am only speaking from experience as a mother of a child at the University of Toulouse 3, Paul Sabatier. The Concours is a peculiarity of France in certain disciplines, where in this case the PASS (Parcours d’Accès Spécifique Santé) can best be described as a national competition in which students take part, to get the prized places to study medicine.

You must understand that in France, public university education is essentially free, and the accommodation is heavily subsidised. If you qualify to get a place in medicine in France, you effectively have the Holy Grail. This year in Toulouse, just over 1200 students took part to try to grab the 202 (exactly!) places on offer. To make it even more complicated, those places include seats for medicine, pharmacy, midwifery and dentistry. So there are only 124 places this year for medicine. This number changes each year and is the “numero apperatus” for this specific university.

What happens if you fail?

If you fail the Concours year you have one last chance to get through, via the LAS method of continuing with your bachelors degree in the minor subject you have chosen, and have another go at the exams at the end of the year. However, once that chance has also expired unfortunately you have to go to another country to try again in medicine. There is a French university in Cluj, Romania (there are other universities in Europe which you can apply to) where a lot of students register to study, although if you do follow this route, you have to pay for it. It costs around 3,600 to 5,000€, not including living costs and accommodation. You have to learn the language, as your stages are based in the country, however the qualification is recognised in Europe.

Parcoursup

To be able to get onto this course you have to understand a few principles. It has a highly selective entry, and even then you might not be able to complete the course. The idea is to get around 16/20 for your Bac to get a good chance to be accepted. Your Bac needs to be science-orientated. My son wasn’t ready to choose the right Bac subjects, and panicked during the summer holidays before his “premier” year as he had opted for the wrong options. We needed to go to the lycée the first week in, and plead for his choices to be changed, to include Maths, SVT (biology-geography), and Physics-chemistry. Luckily after a two-week wait as the classes were already full (36-student limit for classes in France) he had the good luck that one of the students moved due to their father being transferred in the military to another region. He was able to drop the SVT choice after a year, but was able to gain a good mark in it which was used for the Parcoursup applications. He also had to do a small timed online test during Parcoursup, which was also part of the process for accessing the course.

Preparation?

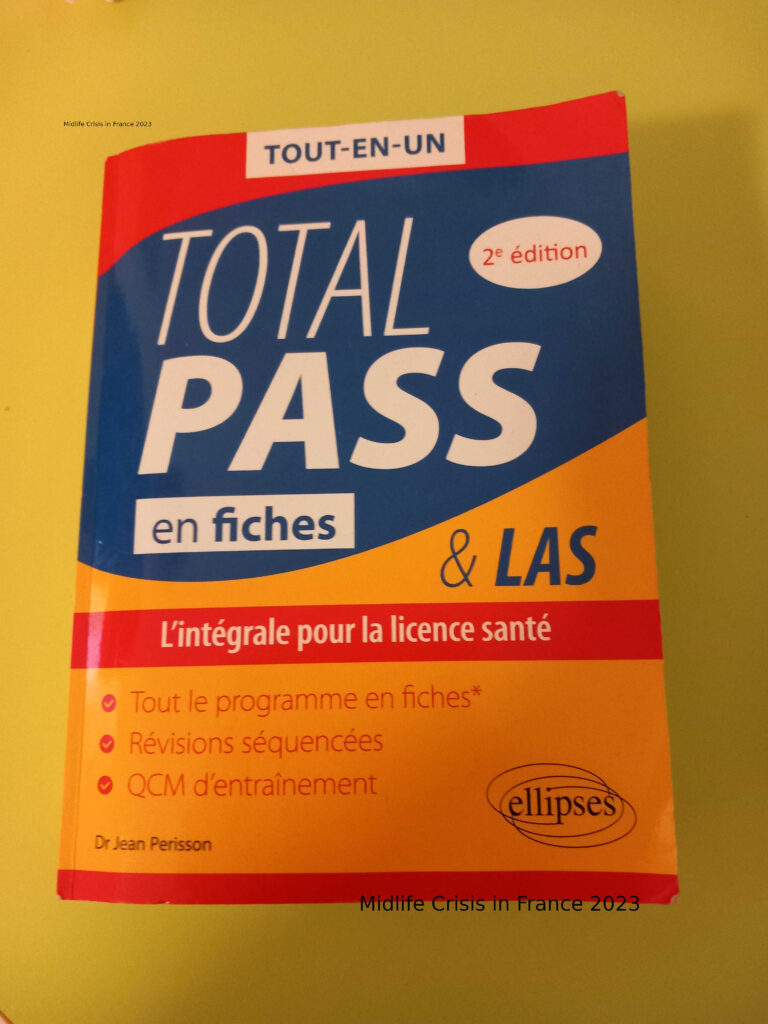

Some students, before taking part in this sacrifice away from normal life for 7 months, do a “prépa”. This can be a one or two-year course (depending on what course you are aiming for) to prepare for the important university year ahead. It could be for engineering to get into a prestigious engineering school, or for students taking (for example) a literature-heavy syllabus to get into a prestigious university, Une Grande Ecole. It is a familiar route that many people have trodden. In medicine a lot of the prépas are private which means you could be paying anything from 3,000 to 10,000€ for the year. A lot of people also get the annals at the beginning of the summer holidays, and decide to prepare during the three months before the school year starts. I have to admit that my son was a bit late in the day wanting to get into medicine, so we did hardly any research before putting it on our Parcoursup choices. We didn’t realise that there is more of a chance to get a place if you look for subjects to study in your educational region. Neither did we realise there were prépas out there, or realise the significance of them. We didn’t even think about buying a book to do some study until the last minute, mid-August. It was when we read the first chapter of this massive door-stop that was apparently just for part of the first semester, we suddenly realised that perhaps we should have started earlier. The statements in the first chapter of trying to pace yourself, create a timetable of your summer holidays and don’t worry if you have not revised everything before the start of term started to make us realise that perhaps there was more to a Concours than we perhaps previously realised. There was also the choice to come two weeks early to start university and have a pre-rentrée to prepare for the course in front of you. My son felt that he would like to stay on holiday and so (on reflection extremely poorly prepared) he entered his first year at university on one of the most difficult courses there is. He has likened it to doing 2 degree courses in 5 months. On reflection I am not really sure even that does it justice.

Lessons

At Toulouse this year they split the massive group of people into four, having two morning groups and two afternoon groups each day. My son was in the afternoon group, which he thought was great as he had it in his head that he could sleep in each morning, cruise to his lectures in the afternoon at 2pm until 6pm, have dinner with friends and then do “a bit of work” in the evening.

The first hour of the term was the welcome talk. Perhaps slightly different to what they were all expecting. Basically it was along the lines of “Great to see that you are here, however only one out of ten of you will succeed. Some of you might end up in hospital, and others might end up with burn out. If you don’t work from day one you will not succeed. “

Rabbit in the headlights

I can remember his little eyes now, a rabbit in a lorry’s headlights and he hasn’t realised that it’s a lorry yet. He still had three hours left of that first day. Those lessons, I think, went by in shock for him and probably for the rest of the students. He recalled he didn’t understand anything the professors were talking about, and I am sure he wasn’t the only one. Another issue with the Concours is that the professors have to complete the programme they have been given, if not they are immediately putting the students at a disadvantage. It puts a lot of pressure on the lecturers to complete the syllabus. This was aptly portrayed by the time a student fainted in the lecture theatre and, instead of the lesson being postponed another day due to the 15 minutes delay, the professor decided to pick up the pace and manage to literally run through the rest of the lecture.

Luckily, all of the lectures were also provided as a printed copy, so if you didn’t understand what the hell the professor was talking about, or if your note taking was not up to scratch, if you ended up panicked and frozen in your chair or just plain fainted and no-one bothered to inform anyone else of this fact, then rest assured, the notes could be found at the end of the day in the student’s digital workstation. Some students who didn’t have to be present at the lectures (if they had no student grants) in the end just didn’t bother turning up and worked at home for most of the course. At Toulouse every Monday students were given the option of practical sessions including practice “exam questions” to answer. This helped give the students an inkling of what they were up against.

Multiple choice

The questions were multiple choice, which immediately in my mind made me think “surely easy?” No. Apparently you had around a minute per question, multiple answers, the finest detail of language, maths or chemical formulas needed, and to top it all off negative points. That meant, if you answered wrongly, you were docked a point. In the first few practices my son was getting negative numbers. The nightmare however continued when there was a session about how best to answer the papers. It all has to be done in black ink, no errors allowed or else you have to start the separate answer sheet again as it was all marked by computer. That session, my son walked out of his first lecture. The suggested method meant he lost his order of questions and answers, and he had to restart from halfway through. He ended up only being able to get a few answers on the paper. I think, however, even that was not the lowest point of the course.

The first few weeks all the students have hope, buoyed up by Bac results and parents and family telling them how wonderful they are. But as question papers came back with pitiful results, no time to ask lecturers questions about what the hell they were talking about, and as the sheer quantity of work and revision kept growing, they all began to feel the pressure. I have to emphasise at this point that when students were given an hour’s lecture on a topic, all of the subject matter had to be memorised in the finest detail. Not only memorised but also understood. So a lot of research and practice time is needed. Even the spellings had to be accurate to the last letter. So much pressure.

Fun first year?

So did my son enjoy his first year at university? I don’t think you could describe this year as a “normal” first year at university. It is a course where you are competing against everyone else in the class, and you are actively relieved when you watch people leaving or failing the course. You also know that you will not see most of the people around you in the following year. Only one person out of ten has any chance of progressing.

First set of exams

The first set of exams at Christmas (no half-term holiday) were preceded by the mocks, which were only ever intended to give the students an impression of timings and atmosphere and perhaps make them realise that they should be revising. I say that because the results of those mocks arrived way after Christmas, not serving any purpose at all to see how well you are doing with relation to the other students. On receiving the results, the students got the double whammy of receiving their results but only been given an ambiguous placement. Incredibly frustrating and perhaps even destabilising as effectively you are competing against yourself for the 7 months. The real exam results themselves ended up in the student’s hands in February, with the sole purpose of keeping the students still in the programme for the second semester. With the arrival of the results came the news that over 600 students had failed their Concours year.

Chatting to a mother on the day of the exams in December, I realised that it was not just my child who was finding the course difficult. We were both worried about their health, sleep, overwork and lack of eating. At this stage my son was putting his alarm for 6am, working sometimes through lunch and dinner, and burning the midnight oil until 12, 1 or even 2 am. Friends? He maybe had the time to see friends three or four times in the 7 months. Sports, hobbies? Impossible. Weekend visits? They were filled with tension as the pressure was on to work and achieve. In the end it was always just a fleeting visit of twelve hours to get his laundry done and shopping bought. Friendship on the course? Sometimes people were there, sometimes not, for weeks on end. On rare occurrences you got news they had quit. Even though after the first session over half of the students failed the Concours, they were still entitled to continue the year and get the university points for the first year if they got the average pass mark. The tension was palpable. The main focus became your placement on the list of admissible students. This position number became the most important number, varying with relation to fractions of a percentage points on your exam results.

Final exams

The final exams a fortnight ago were held over two complete days. The first day included the normal medical courses and the second day, was the exams of the minor subject that all the students were obliged to take. My son took his favourite subject, Maths. If the student failed the Concours, they could go into the second year of their bachelors with the minor of their choice. This meant students were obliged to complete the Parcoursup form on the internet with their fail-safe choices. I have to say it was filled in with not much thought, as each minute of each day counted now for study and no-one wants to think of Plan B after consecrating a huge part of their lives to study.

Relief

So what can he expect now? Well, of course a well deserved rest. I can understand why at the end of the last semester one professor warned against taking their health lightly, mentioning statistics of the amount of students who do this Concours ending up in hospital each year.

Unfortunately only half of the first 124 students will get through immediately and will be high and dry. The rest of the students, about 200 of them have the “oral” to look forward to. This will be the decider of their placement on the board, and will be the “be-all and end-all” for the Concours year. In France you only get one chance to do this. You do get the opportunity a few weeks in to stop the course and hence be able to try again another year. However after that specific date, you give up the right to do this. If you do fail the Concours but pass the first year of university, there is one other route to get in, the LAS route.

So what about the oral?

This is where things get complicated. Only half of the allotted places for pure medicine get allocated to the highest placed students. That means for this year, 2023, only 62 places after the main Concours exam become available for the top 62 people. They are the “Grand Admissibles”. They get the “golden ticket” to go straight through to year two. Everyone else who has passed both semesters will have to take the “grand oral”.

“Fine,” a lot of you are thinking. A talk can’t be that bad. Well true if there was a theme. But, wait for it! Yes, you have guessed it. The students are presented with situations only as they walk through into the examining room, and have five minutes to present a talk explaining how they would react to certain “real-life” situations. For example, “how would you react if you were confronted with a man holding a knife in the street”. They then get quizzed on their answer for another five minutes, evaluated on their talk and their responses, and not only that but they have to go through it all again later (a slightly lengthier one) on the same day! This gives them two new marks, which count for 30% of their overall mark of the year. This can cause large fluctuations in original positions, important as in the whole year only the top ‘classement’ of 202 are allowed in (minus of course the 62 students that have already made it). It won’t be until end of June that he can finally relax.

Was it the right Parcoursup choice?

That is dependant on if you really want to do medicine or not? For my son, who wanted to give it a go, Toulouse seemed the obvious option. He is still only 17 so being close to home meant we could still keep an eye on him, and he had the option of coming as home as often as he wished during a momentous time in his life.

There will be some of you thinking, surely it is easier to go to the UK or somewhere else. Maybe. However, in France the university education is free, the accommodation and other services hugely subsidised and also our lives are here. If you take a cold hard look at the figures, over a tenth of the students pass the concours year and get into medicine. Reading the statistics of universities in the UK, that is not too far offf the same percentage of people who get onto and pass their first year of medicine. So in the end how is it that different? Yes it is an extra year, but once you are in, the fail rate per year is pretty low.

In the end, as parents who have watched their child go through the first Concours year, you can’t help but conclude that medicine is a course that you have to have the motivation, strength of character and determination to get through. It takes a particular type of person. So huge amounts of respect to all those people that have taken this journey. Whether it will be my son’s path, we won’t know for a while. To be honest I think he is just thankful he’s survived so far.

And so are we.

MidLife Crisis In France

COPYRIGHT Ⓒ 2023